Navayana (Devanagari: नवयान, IAST: Navayāna) means “new vehicle” and refers to the re-interpretation of Buddhism by B. R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar was born in a Dalit (untouchable) family during the colonial era of India, studied abroad, became a Dalit leader, and announced in 1935 his intent to convert from Hinduism to Buddhism. Thereafter Ambedkar studied texts of Buddhism, found several of its core beliefs and doctrines such as Four Noble Truths and “non-self” as flawed and pessimistic, re-interpreted these into what he called “new vehicle” of Buddhism. This is known as Navayana, also known as Bhimayāna after Ambedkar’s first name Bhimrao. Ambedkar held a press conference on October 13, 1956, announcing his rejection of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, as well as of Hinduism. Thereafter, he left Hinduism and adopted Navayana, about six weeks before his death.

In the Dalit Buddhist movement of India, Navayana is considered a new branch of Buddhism, different from the traditionally recognized branches of Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Navayana rejects practices and precepts such as renouncing monk and monasticism, karma, rebirth in afterlife, samsara, meditation, enlightenment and Four Noble Truths considered to be foundational in the Buddhist traditions. It radically re-interprets what Buddhism is, revises the original Buddha teaching to be about class struggle and social equality.

Ambedkar called his version of Buddhism Navayana or Neo-Buddhism. His book, The Buddha and His Dhamma is the holy book of Navayana followers. Followers of Navayana Buddhism are generally called “Buddhists” (Baud’dha) as well as “Ambedkarite Buddhists”, “Neo-Buddhists”, and rarely called “Navayana Buddhists”.

Origins

Ambedkar was an Indian leader influential during the colonial era and the early post-independence period of India. He was the fourteenth child in an impoverished Maharashtra Dalit family, who studied abroad, returned to India in the 1920s and joined the political movement. His focus was social and political rights for the Dalits. To free his community from religious prejudice, he concluded that they must leave Hinduism and convert to another religion. He chose Buddhism in the form of Navayana.

Doctrines and concepts

In 1935, during his disagreements with Mahatma Gandhi, Ambedkar announced his intent to convert from Hinduism to Buddhism.[3] Over the next two decades, Ambedkar studied texts of Buddhism and concluded that several of the core beliefs and doctrines of mainstream Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism were flawed, pessimistic and a corruption of the Buddha’s teachings. In particular, according to Eleanor Zelliot – a professor of History specializing on Dalit community in India, Ambedkar found the following beliefs and doctrines of Buddhism as problematic:

Buddha’s parivaja

The Buddhist tradition believes that the Buddha one day saw a sick man, an old man and a dead body in sequence, then he left his princely life and sought insights and a way out of human suffering. According to Ambedkar, this was absurd. He proposed that the Buddha likely sought insights because he was involved in “making peace among tribes”..

Four Noble Truths

Ambedkar believed that this core doctrine of Buddhism was flawed because it denied hope to human beings. According to Ambedkar, the Four Noble Truths is a “gospel of pessimism”, and may have been inserted into the Buddhist scriptures by wrong headed Buddhist monks of a later era. These should not be considered as Buddha’s teachings in Ambedkar’s view..

Anatta, Karma and Rebirth

These are other core doctrines of Buddhism. Anatta relates to no-self (no soul) concept. Ambedkar believed that there is an inherent contradiction between the three concepts, either Anatta is incorrect or there cannot be Karma and Rebirth with Anatta in Ambedkar’s view.[4] Other foundational concepts of Buddhism such as Karma and Rebirth were considered by Ambedkar as superstitions..

Bhikshu

A Bhikshu is a member of the monastic practice, a major historic tradition in all schools of Buddhism. According to Ambedkar, this was a flawed idea and practice. He questioned whether a Bhikshu tradition was an attempt to create “a perfect man or a social servant”, states Zelliot..

Nirvana

According to Navayana, nirvana is not some other-worldly state of perfect quietude, freedom, highest happiness, nor soteriological release and liberation from rebirths in saṃsāra. In Ambedkar’s view, nirvana is socio-political “kingdom of righteousness on earth” in which people are “freed from poverty and social discrimination and empowered to create themselves happy lives”, state Damien Keown and Charles Prebish.

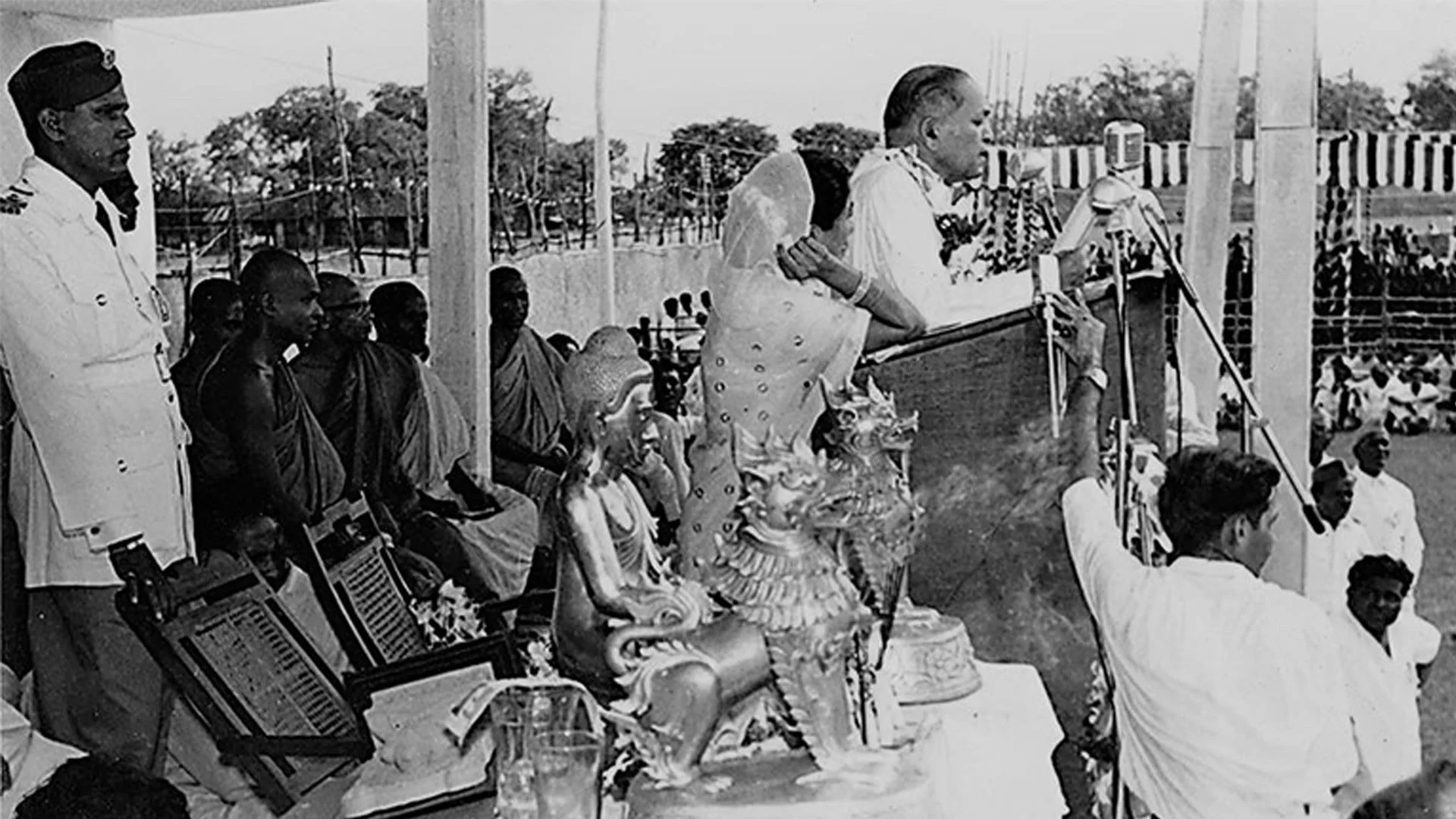

Conversion

Ambedkar delivering a speech during mass conversion in Nagpur, 14 October 1956.

Ambedkar re-interpreted Buddhism to address such issues in his mind and re-formulated the traditional teachings of Buddhism into a “new vehicle” called Navayana. Navayana dhamma doctrine as propounded by Ambedkar, states Yashwant Sumant, “does not situate morality in a transcendental [religious] domain”, nor in “a civil association, including the state”. Dhamma is derived from and the guiding principle for social conscience.

Navayana Buddhism began in 1956 when B. R. Ambedkar adopted it, and 380,000 Dalit community members converted to Navayana from Hinduism on 14 and 15 October 1956. After that on every year 14 October is celebrated as Dhammachakra Pravartan Day at Dikshabhoomi, Nagpur:

I will accept and follow the teachings of Buddha. I will keep my people away from the different opinions of Hinayana and Mahayana, two religious orders. Our Buddhism is a Neo-Buddhism, Navayana.

— Babasaheb Ambedkar, Press interview on 13 October 1956 at Sham Hotel, Nagpur

Scripture and practice

The writings of Ambedkar were posthumously published as The Buddha and His Dhamma, and this is the scripture for those who follow Navayana Buddhism. Among the Navayana followers, state Keown and Prebish, this is “often referred to as their ‘bible’ and its novel interpretation of the Buddhist path commonly constitutes their only source of knowledge on the subject. In this scripture of the Navayana tradition, there are no doctrines of renunciation and monastic life, or karma, or rebirth, or jhana (meditation), or nirvana, or realms of existence or Four Noble Truths – ideas found in the major traditions of Buddhism. The text presents the Buddha as teaching a social empowerment framework. Ambedkar’s text on Navayana states that this was what the true Buddha taught and which escapist Buddhist monks had distorted, through misguided interpolations, over Buddhism’s long history.

- R. Ambedkar is regarded as a bodhisattva, the Maitreya, among the Navayana followers. In practice, the Navayana followers revere Ambedkar, states Jim Deitrick, as virtually on par with the Buddha. He is considered as the one prophesied to appear and teach the dhamma after it was forgotten; his iconography is a part of Navayana shrines and he is shown with a halo. Though Ambedkar states Navayana to be atheist, Navayana viharas and shrines feature images of the Buddha and Ambedkar, and the followers bow and offer prayers before them in practice. According to Junghare, for the followers of Navayana, Ambedkar has become a deity and is devotionally worshipped.

Reception

Ambedkar’s re-interpretation of Buddhism and his formulation of Navayana has attracted admirers and criticism. The Navayana theories restate the core doctrines of Buddhism, according to Eleanor Zelliot, wherein Ambedkar’s “social emphasis exclude or distort some teaching, fundamental to traditional and canonical Buddhism”. Anne Blackburn states that Ambedkar re-interprets core concepts of Buddhism in class conflict terms, where nirvana is not the aim and end of spiritual pursuits, but a preparation for social action against inequality:

Ambedkar understands the Buddha’s teaching that everything is characterized by Dukkha or unsatisfactoriness, as referring specifically to interpersonal relations. In one instance Ambedkar presents a dialogue in which the Buddha teaches that the root of dukkha is class conflict and asserts elsewhere that “the Buddha’s conception of Dukkha is material.” Nibbana (Skt. nirvana) the state or process which describes enlightenment, is considered [by Ambedkar] a precursor for moral action in the world and explicitly associated with a non-monastic lifestyle. Nibbana “means enough control over passion so as to enable one to walk on the path of righteousness.” Ambedkar’s interpretation of dukkha and Nibbana implies that moral action, for which Nibbana is preparation, will rectify the material suffering of inequality.

— Anne Blackburn, Religion, Kinship, and Buddhism: Ambedkar’s Vision of a Moral Community.

Ambedkar considered all ideas in Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism that relate to an individual’s merit and spiritual development as insertions into Buddhism and something that “cannot be accepted to be the word of the Buddha”. Buddhism, to Ambedkar, must have been a social reform movement. Martin Fuchs states that Ambedkar’s effort is to be admired as an attempt to seek a “post-religious religion” which transcends distinctions and as being driven by the “reasonable principle of sociality”, not in the sense of spiritual doctrines, philosophical speculations, and existentialist questions.

According to Blackburn, “neither view of traditional Buddhism — as a social reform movement or as some other stable entity interpreted (or misinterpreted) from a social reform perspective — is historically accurate”, thereby placing Navayana theories to be ahistorical though it served as an important means to Dalit political mobilization and social movement. Scholars broadly accept that the depictions of the Buddha as a caste or social reformer are inaccurate. Richard Gombrich, an Indologist and a professor of Buddhist Studies, states that there is no evidence that the Buddha began or pursued social reforms or was against a caste system, rather his aim was at the salvation of those who joined his monastic order. Modernist interpreters of Buddhism states Gombrich, keep picking up this “mistake from western authors”, a view that initially came into vogue during the colonial era. Empirical evidence outside of India, such as in the Theravada Buddhist monasteries of the Sinhalese society, suggests that caste ideas have been prevalent among the sangha monks, and between the Buddhist monks and the laity. In all canonical Buddhist texts, the Kshatriyas (warrior caste) are always mentioned first and never other classes such as brahmins, vaishyas, shudras, or the untouchables.

The novel interpretations and the dismissal of mainstream doctrines of Buddhism by Ambedkar as he formulated Navayana has led some to suggest that Navayana may more properly be called Ambedkarism. However, Ambedkar did not consider himself as the originator of a new Buddhism but stated that he was merely reviving what was original Buddhism after centuries of “misguided interpretation” by wrong-headed Buddhist monks. Others, states Skaria, consider Ambedkar attempting a synthesis of the ideas of modern Karl Marx into the structure of ideas by the ancient Buddha, as Ambedkar worked on essays on both in the final years of his life.

According to Janet Contursi, Ambedkar re-interprets Buddhist religion and with Navayana “speaks through Gautama and politicizes the Buddha philosophy as he theologizes his own political views”.

Status in India

According to the 2011 Census of India, there are 8.4 million Buddhists in India. Navayana Buddhists comprise about 87% (7.3 million) of the Indian Buddhist community, and nearly 90% (6.5 million) of all Navayana Buddhists in India live in Maharashtra state. A 2017 IndiaSpend.com report on census data says “Buddhists have a literacy rate of 81.29%, higher than the national average of 72.98%”, but it does not distinguish Navayana Buddhists from other Buddhists. When compared to the overall literacy rate of Maharashtra state where 80% of Buddhists are found, their literacy rate is 83.17% or slightly higher than the statewide average of 82.34%.

According to Jean Darian, the conversion to Buddhism and its growth in India has in part been because of non-religious factors, in particular, the political and economic needs of the community as well as the needs of the political leaders and the expanding administrative structure in India. According to Trevor Ling and Steven Axelrod, the intellectual and political side of the Navayana Buddhist movement lost traction after the death of Ambedkar.

Festivals

Ambedkar Jayanti, Dhammachakra Pravartan Day and Buddha’s Birthday are three major festivals of Navayana Buddhists.